Corporate Venture Capital (CVC) is a highly popular approach to corporate innovation: This is the large organization’s take on traditional Venture Capital funding, supplying capital in exchange for equity. Acting as an investor in the ecosystem is a powerful choice. As a literal capitalist, your firm becomes a magnet for startups with technologies, services or business models tied to your industry. Your special domain expertise makes you an especially attractive partner and may make you especially good at spotting good investments.

CVCs are often, but not always, created as separate entities with a separate balance sheet, to simplify taxes as well as to separate the ups and downs of venture capital from the main firm’s quarterly reporting to shareholders. CVCs always have two goals: One goal is financial, and the other is strategic.

The financial goal is straightforward, and precisely similar to traditional VC — make money directly from investment as the stock price increases. One significant strategic goal is learning: Strategic CVCs participate in the capital market in the relevant sector in order to understand what’s happening from a business, customer and/or technology point of view. Other learning themes include environmental impact or relevant social trends. Strategic goals may include influencing the industry, brand visibility, or filling the technology pipeline — the CVC takes a huge number of startup meetings, and some candidates deemed not appropriate for broader investment may be well suited to other partnership opportunities such as proofs of concept or licensing.

A CVC that is primarily strategic limits its investment appetite to strategically relevant companies. A CVC that is primarily financial can explore more broadly but provides less learning value along the journey. Generally speaking, CVCs carry both goals but lean more heavily into one.

CVCs, like traditional VCs, invest in a portfolio of companies. Theoretically one giant success covers any losses from startups that fail to reach a high-multiple exit. Like VCs, CVCs help their portfolio companies succeed through a significant investment of dollars, as well as making connections. Because CVCs are tied to the parent company at least by name, they may be able to offer resources that traditional VCs can’t — this includes brand connection and might also include specialized expertise, equipment, customer lists, etc.). Some CVCs join the startup’s business as board observers or acting board members.

Startups may be more or less interested in CVC investment depending on how they perceive the large firm’s brand or partnership reputation.

In Open Innovation Works, we propose seven key matters for large firms to contemplate as they decide which partnership engagement engines work for them. Here’s how CVCs stack up:

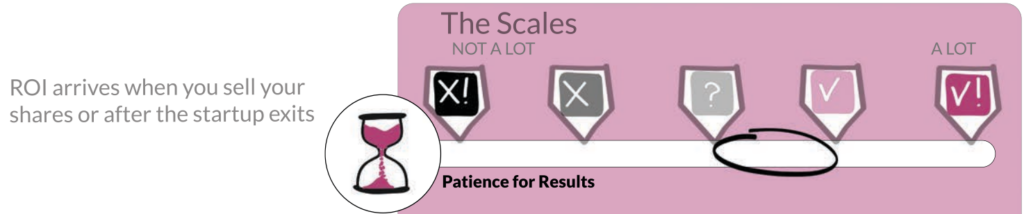

Patience for Results: between 3 and 4

How long you’ll wait for results for a CVC depends on which goals you’re emphasizing. Strategic goals begin to pay off immediately, whereas financial goals can take 3, 5 or 10 years or more depending on the industry. That’s because the return on investment typically arrives when the startup “exits” — becomes a public company; or is purchased. That’s when the stock can be sold for a high multiple.

CVC is a good fit for organizations whose open innovation initiatives have a few years of grace before needing to demonstrate financial results.

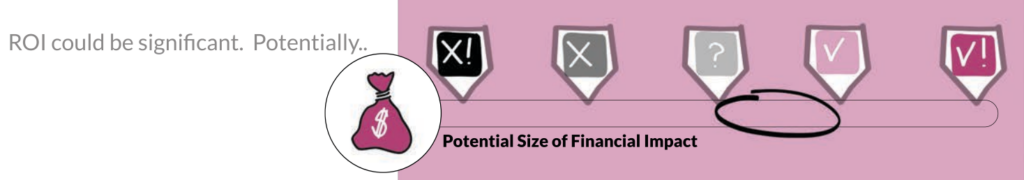

Potential size of financial impact: between 3 and 4

Relative to other partnership engines, Corporate Venture Capital (CVC) activities wield substantial potential for influencing the financial landscape of companies. By strategically investing in high-financial-potential external startups at a sufficiently early stage, corporations not only gain access to cutting-edge technologies and novel business models but also may reap considerable financial rewards if all goes well. Successful CVC initiatives can lead to lucrative exits through acquisitions or initial public offerings (IPOs), providing a substantial return on investment.

One notable example of how CVC can result in high financial impact is Google Ventures’ investment in the ride-sharing pioneer, Uber. In 2013, Google Ventures participated in a significant funding round for Uber, marking a strategic move to align with the innovative disruptions occurring in the transportation industry. This investment not only provided Google with a foothold in the burgeoning sector but also contributed to Uber’s rapid expansion. Eventually, Uber’s valuation soared, making it one of the most valuable startups globally. When Uber went public in 2019, Google Ventures (rebranded as GV) realized 20X returns on its initial investment – all in the span of only 6 years. Note that Uber showed a profit for the first time in 2023!

The success of this CVC initiative not only yielded significant financial gains for Google but also showcased the strategic prowess of CVC in identifying and supporting disruptive technologies that can redefine industries and create substantial value for both the invested company and the corporate investor. Another concept showcased in this story: If you’re able to make a very substantial investment, CVC, like venture capital in general, can be somewhat self-fulfilling: By investing, you put a great deal of energy behind an idea. Ideas in which you do not invest do not receive that energy.

That said: It’s important to be aware that successes like the Google story are rare. Even in highly successful CVC endeavors, most individual CVC investments do not pay off. It’s also worth noting that the relationship between CVCs and their investees can be complex. The Google/Uber story itself went sour due to IP and staffing disputes even before the exit. Perhaps all parties went crying to the bank — this type of tension doesn’t need to be a show-stopper, it’s just something to be prepared for.

If your organization is very keen on financial impact from open innovation, is willing to risk some capital up front, and can stand the heat of high-stakes partnerships, consider creating a CVC arm.

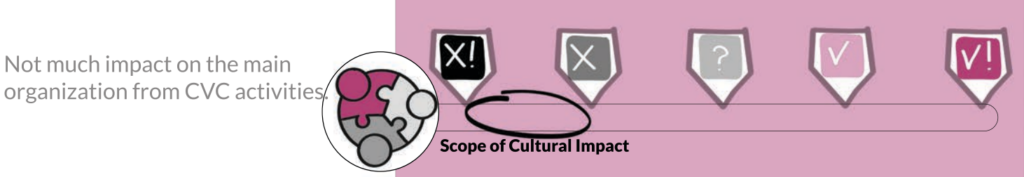

Scope of cultural impact: between 1 and 2

Corporate Venture Capital groups (CVCs) typically operate externally to the core organizational structure — in fact quite often they are created as completely separate organizations with separate premises and balance sheets. That’s because the balance sheet of a CVC looks volatile: Large amounts of money go out in a short period of time (investment). Then nothing happens for a long time while the investments develop. Ultimate profits and losses arrive over years, not over quarters. Tax planning can also drive large organizations to keep the CVC as a separate entity. When the CVC is separate, there is little or no interaction between the staff of the CVC and the staff of the main organization, and therefore little or no impact on culture.

Even when not formally separated, the work, expertise, goals and timelines of the CVC staff are very different from the core work of the parent company. These differences make it unlikely that the CVC will impact the culture of the parent company in any significant way. With extensive work to ensure cultural ties, it would be possible to create a cultural influence, but not without investing additional time and money into this function.

While CVCs can contribute valuable external perspectives, networks, and tech-awareness, their influence on the deeply ingrained cultural aspects of the organization is likely to be limited. Any small influence will arrive through leadership communications to employees, or through staff members who are called upon to assess the investments.

Choose CVC if you’re happy with your core culture, or if you’re happy to address cultural concerns in a different way.

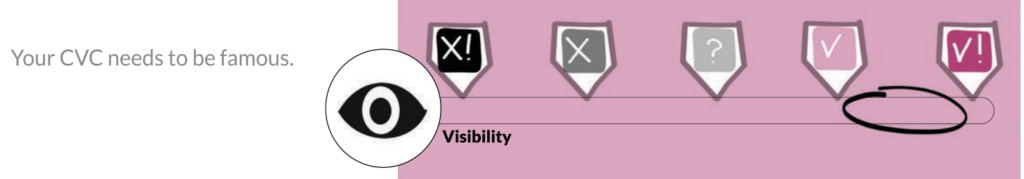

Visibility: between 4 and 5

Corporate Venture Capital arms are highly visible in their nature. To attract investible startups, CVCs need to put themselves squarely in the spotlight within the startup ecosystem. By doing so, they also make themselves highly visible to shareholders, employees, competitors and customers. If you want everyone to know you’re involved in open innovation, estabIishing a CVC is a good way to catch their eye. As with a startup accelerator, the marketing of your CVC is inherently the marketing of your organization’s commitment to innovation, collaboration, and staying at the forefront of trending technologies and business models.

Corporate Venture Capital can serve as a compelling and impactful open innovation engine for organizations keen on public interest and attention. And if you’re not keen on public interest and attention, choose a different engine.

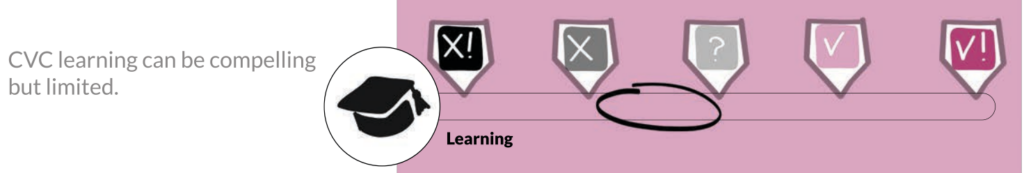

Learning opportunity: between 2 and 3

Establishing a CVC arm can certainly yield valuable insights for your company by forcing attention to the experience of specific startups as they attempt to impact an industry. However, the depth of these learnings may be limited. This limitation stems from the fact that usually CVCs live outside the core of the company, so it’s a challenge to drive insights into organizational strategy. In addition, the CVC’s view inside of its portfolio company is somewhat limited. Depending on the size of investment, you may have an opportunity to observe or even guide at the board level, but you may not be invited into the lab, onto the manufacturing floor or into the business design conversations.

If your organization prioritizes extensive learning as a core objective in its open innovation, consider alternative approaches that offer more direct and profound knowledge exchange.

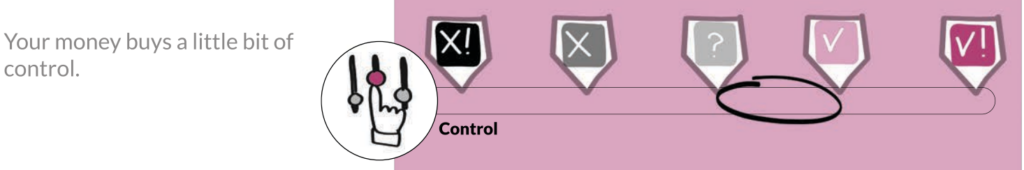

Degree of corporate control: between 3 and 4

In a CVC arrangement, the CVC and the startup are partners, with separate swimlanes. The CVC supplies dollars and the startup attempts to turn those dollars into commercial success. The large organization doesn’t get to make decisions on behalf of the startup. That said, the CVC has a fair amount of influence through the offer of various types of in-kind assistance including strong advice. Depending on the size of the investment, the CVC may place a staff person on the startup’s board, typically as an observer. The main organization itself sits further back and can say yes or no to the entire enterprise, perhaps yes or no on specific investments depending on the structure.

A CVC is a good option for your organization if you’re willing to cede a certain amount of control to your startup partners.

Resources required: between 4 and 5

Engaging in Corporate Venture Capital (CVC) constitutes a money-intensive endeavor, with the primary emphasis on financial resources rather than other forms of support. The size of a Corporate Venture Capital (CVC) budget can vary widely and is influenced by factors such as the objectives of the CVC, the industry, and the scale of the parent company. CVC budgets typically range from tens of millions to several hundred million dollars. Some large corporations allocate significant resources to their CVC activities, allowing them to make substantial investments in startups and emerging technologies. However, the budget size also depends on the risk appetite and financial capacity of the company, as well as the specific goals it aims to achieve through its CVC initiatives. The budget for CVC is a strategic decision based on the company’s overall investment strategy and its commitment to fostering innovation and growth.

For instance, Intel Capital, the venture capital arm of Intel Corporation, has historically been recognized as a prominent CVC player. Founded back in 1991, Intel Capital has managed funds in the range of hundreds of millions to over a billion dollars. For example, in 2020 alone they invested in between $300 and $500 million dollars in promising technology companies. Intel Capital’s significant budget has allowed it to make numerous investments in startups and emerging technologies across different sectors, showcasing the substantial financial commitment that some corporations allocate to their CVC initiatives. For perspective, note that the market cap for Intel sits at upwards of $130 billion dollars as we write.

CVC serves as an excellent open innovation mechanism for companies that are comfortable with financial risks and have the financial capacity to support such endeavors.

Why should you choose this engine?

Through CVC, a large organization gains access to external innovation, cutting-edge technologies, and disruptive business models by investing in startups. This not only diversifies the company’s business but also fosters strategic partnerships, potentially leading to collaborations or acquisitions that strengthen market positions.

Moreover, CVC activities offer valuable market insights and enhance the company’s agility by staying attuned to dynamic industry trends. Beyond the business benefits, a CVC arm can attract entrepreneurial talent, contribute to talent retention, and position the company as an innovation leader, conferring a competitive advantage.

While financial gains are not the sole focus, successful CVC initiatives can yield profitable exits, further solidifying the company’s position in the market. Overall, building a CVC arm aligns with a forward-thinking approach, positioning the company for sustained success in a rapidly evolving business landscape.

Why shouldn’t you choose this engine?

CVC initiatives demand significant financial resources and the ability to lay out cash for an extended period of time while investments mature. Investing in startups entails significant risk — most CVC investments do not break even, let alone bring significant value. The purpose is to aggregate a portfolio of investments in hopes that at least one will do well, and there’s no guarantee. Don’t build a CVC if you can’t make the case for risk to your stakeholders.

The external and independent nature of CVCs can also pose challenges in integrating their activities with the company’s core operations, potentially leading to lost learning opportunities, or worse, cultural clashes and strategic misalignment.

Managing a CVC effectively requires specialized skills and expertise, and companies lacking experience in venture investing may find it challenging to navigate the complexities of the startup ecosystem. This can be addressed by hiring outside expertise, however the outside expert may not understand the corporate environment in general or your organization in particular.

If you’re an innovation leader in a large firm, you should almost certainly be partnering with startups in some way. Is a CVC the right engine for you?